The manager of The Argillet Collection shares about growing up alongside the famous French Surrealist artist.

Text by: Luo Jingmei

Photography – courtesy of Bruno Gallery

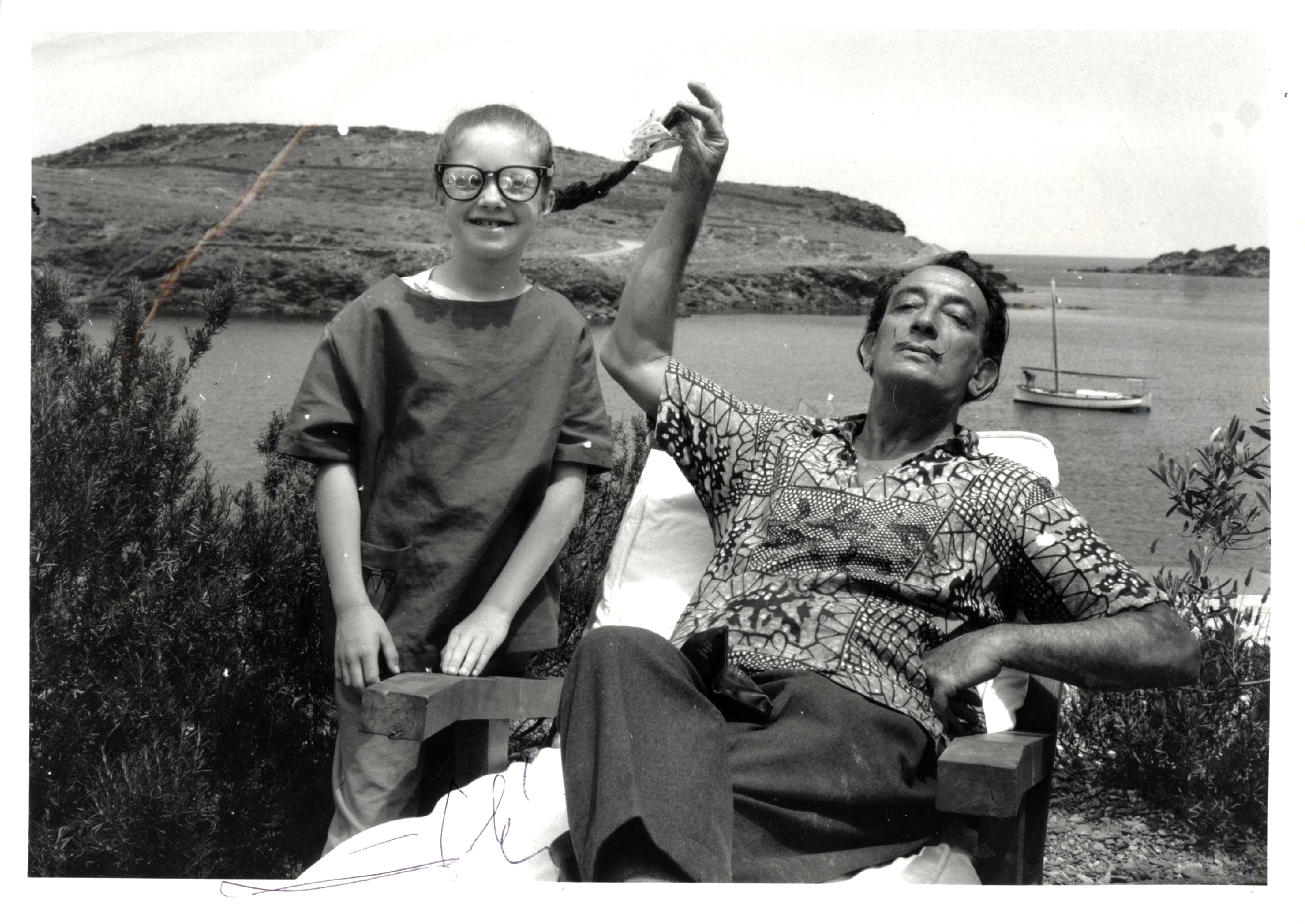

It is not everyday that one can take a photograph with Salvadore Dali, but Christine Argillet has taken many. In fact, she has spent plenty of time with the famous Surrealist artist in her childhood between the ages of five and 17. Argillet’s father was Pierre Argillet, one of Dali’s publishers and a close collaborator for over 40 years.

Her father often took her to meetings with Dali, and the Spanish artist would sometimes come to their home in Port Lligat, Spain to meet with her father. Hence, she had a front-row perspective to the relationship between the two men and also a genuine understanding of Dali’s personality. “Dali was so much fun [and full] of surprises. There was a friendship between the two and an immense respect for each other,” she comments.

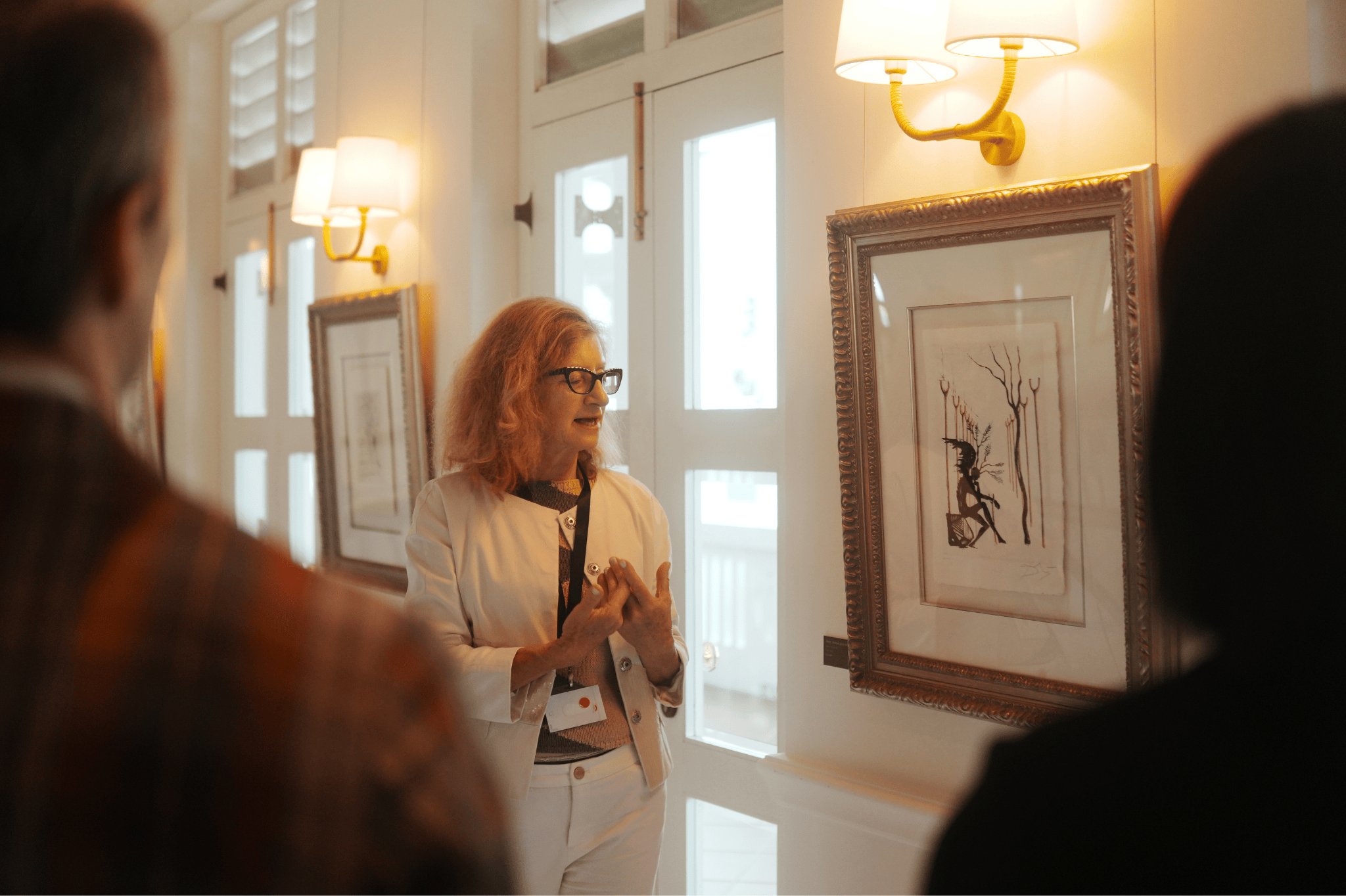

The manager of The Argillet Collection was in Singapore in September for the opening of an exhibition at the Bruno Gallery and Capella Singapore that is now on until 16 November. More than 100 etchings printed from copper plates, as well as some tapestries, are on display. They have made their rounds in showcases around the world but their permanent home is at the Museum of Surrealism in Melun, France, and the Dali Museum in Figueres, Spain, where the artist was born.

This collection is a special one, reflecting the united interests of both the publisher and artist. It also shows a different style by the artist who is mostly known for his paintings, such as The Persistence of Memory featuring his famous melting clocks. “This is immediate, spontaneous,” says Argillet on the etchings, printed from copper plates that Dali scratched on.

The elder Argillet and Dali were in sync with regard to interests, such as curiosity of global cultures, psychoanalysis and avant-garde theories like Dadaism, as well as writings of Goethe, Freud and Sacher-Masoch. Argillet herself is a great storyteller, and beguiled journalists with personal encounters of the great artist who appeared as a striking dandy, with slick gelled hair and a trademark moustache.

She describes Dali as having boundless creative energy that would take him from one project to another, working on everything from art and filmmaking to jewels, and working with anybody – from fellow artists to scientist and personalities like Walt Disney and Elvis Presley.

“It was very difficult to catch him and keep him on one topic so you had to be very prompt,” she mentions. Her father, being aware of this, constantly reined him in, enabling the collections to be created. “Many times, [Dali] would be in a hurry and had not finished working on a project with my father and would need to leave , and my father would run behind him, saying, “I need two plates to finish the project!” Argillet muses in recollection. “Or Dali would be doing an interview and working on the plates [at the same time], and my father would be pale, thinking, ‘What is he going to do?’” But at the end, Dali always produced wonderful work, she says.

She relates a tale that left her father fuming. Dali had arrived at a public crowd of international guests to do a public showcase. “My father sees him and says, ‘there is something bizarre in his eyes; they look strange,” Argillet recollects. Dali went on stage, dashed a few strokes on the copper plate and left. “My father runs after him but Dali says, ‘I’ve finished’. My father tries to stop him, grabbing his jacket,” Argillet narrates.

Dali left and the father explained to the crowd that the artist was not feeling well. The next day, he called and asked her father to bring the copper plate to his hotel. “I had no school so my father brought me. It was very cold between them. Opening the paper [wrapping the drawing], my father says, ‘well, [the drawing] looks like a wool ball.’ Dali looks at it and says, ‘that’s not what I drew the other night,’” Argillet shares.

The artist took the plate and continued working on it, producing an etching of two women jumping into the waves. As for Dali’s strange behaviour at the public showcase, Argillet laughs and explains that it was the late-60s and he was working on the Hippies series with her father. He had decided to try LSD that night to calm his nerves. “He was a very shy man, which many people don’t know about,” she says. “He was on drugs that day. It was a fun story.”

Yet, while he was eccentric, Dali was also humorous. In doing a ‘portrait’ of Mao Zedong, Mao’s suit dominated the plate – minus the head. “Dali said, ‘the man is so big that he didn’t fit on the plate,” mentions Argillet. “He was joking.” Toward the end of their collaboration at around 1973, Dali stopped etching on copper plates as it was damaging he eyes. “Working on the shiny plates was making him cry; he stopped at that very moment,” says Argillet.

Her father and Dali went on to collaborate on other mediums such as porcelain plates and tapestries. Regardless of Argillet’s personal experiences with Dali, she shares the same sentiment as many others of his genius. She says thoughtfully, “He had this capacity, this skill that was extraordinary, and this very expert way of working.”